45 Il tempo per raggiungere un oggetto è funzione della distanza e della dimensione dell'oggetto

Sintesi del contesto di applicazione

Situazione: normale utilizzo dell'interfaccia.

Problema: funzioni importanti non sono immediate e accessibili quanto altre che sono secondarie. |

Accorgimenti in sede progettuale: Posizionare elementi importanti più vicino e aumentarne la dimensione. Sfruttare i punti limite di un riquadro (angoli e bordi), ingrandire pulsanti fondamentali, evitare bordi non cliccabili tra toolbar e bordo schermo. Target multipli implicano la somma dei tempi di ciascun target. La diffusione degli smartphone con schermi piccoli, di fatto, non ha modificato la sostanza di questa legge. Effettuare test a cronometro.

|

Stato dell'analisi

Completa. Applicazione ai prodotti leggermente fuori tema.

Completa. Applicazione ai prodotti leggermente fuori tema.

Applicazione del principio

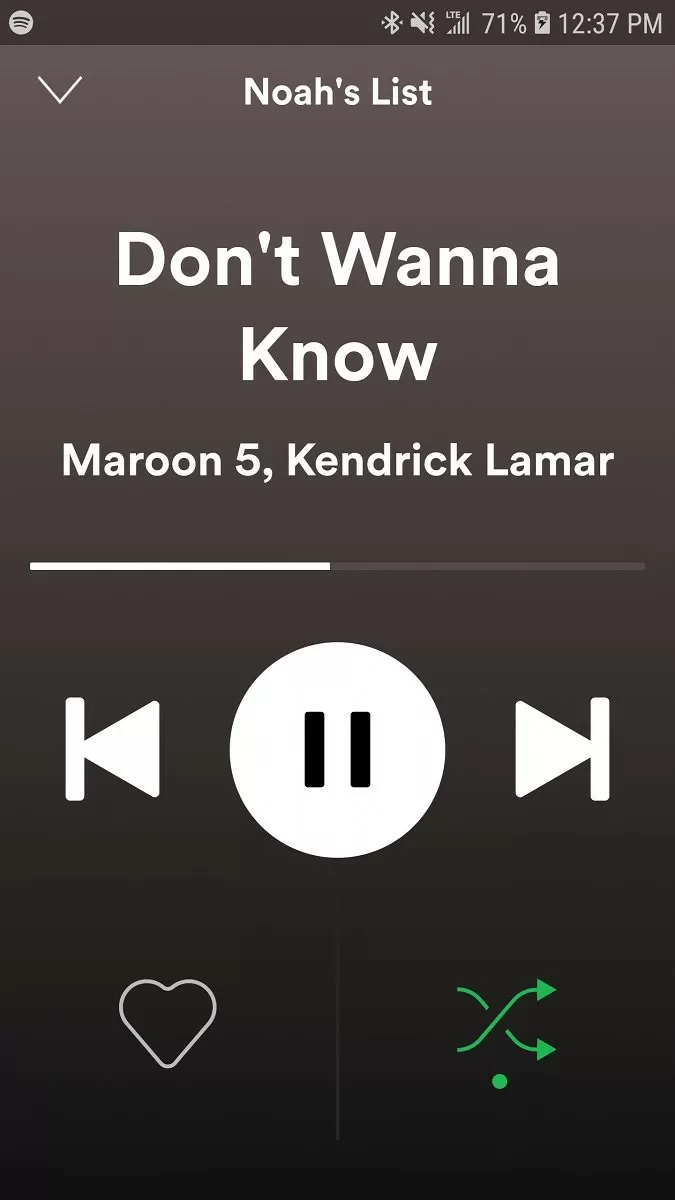

La legge di Fitts calcola il tempo impiegato per muoversi rapidamente da un punto iniziale a un'area con una determinata estensione. Applicata all’interfaccia si può tradurre con la necessità di avvicinare ed ingrandire i comandi principali, per raggiungerli al meglio in pochissimo tempo, ad esempio f.01 Spotify rende gli elementi raggiungibili con una sola mano, in modo che l’utente possa selezionare comodamente qualsiasi pulsante che serve nell’immediato, dunque fermare la musica, cambiare canzone o metterla nei preferiti. Inoltre quando si è in auto, un’opzione rende i pulsanti ancora più grandi per non distrarre la guida.

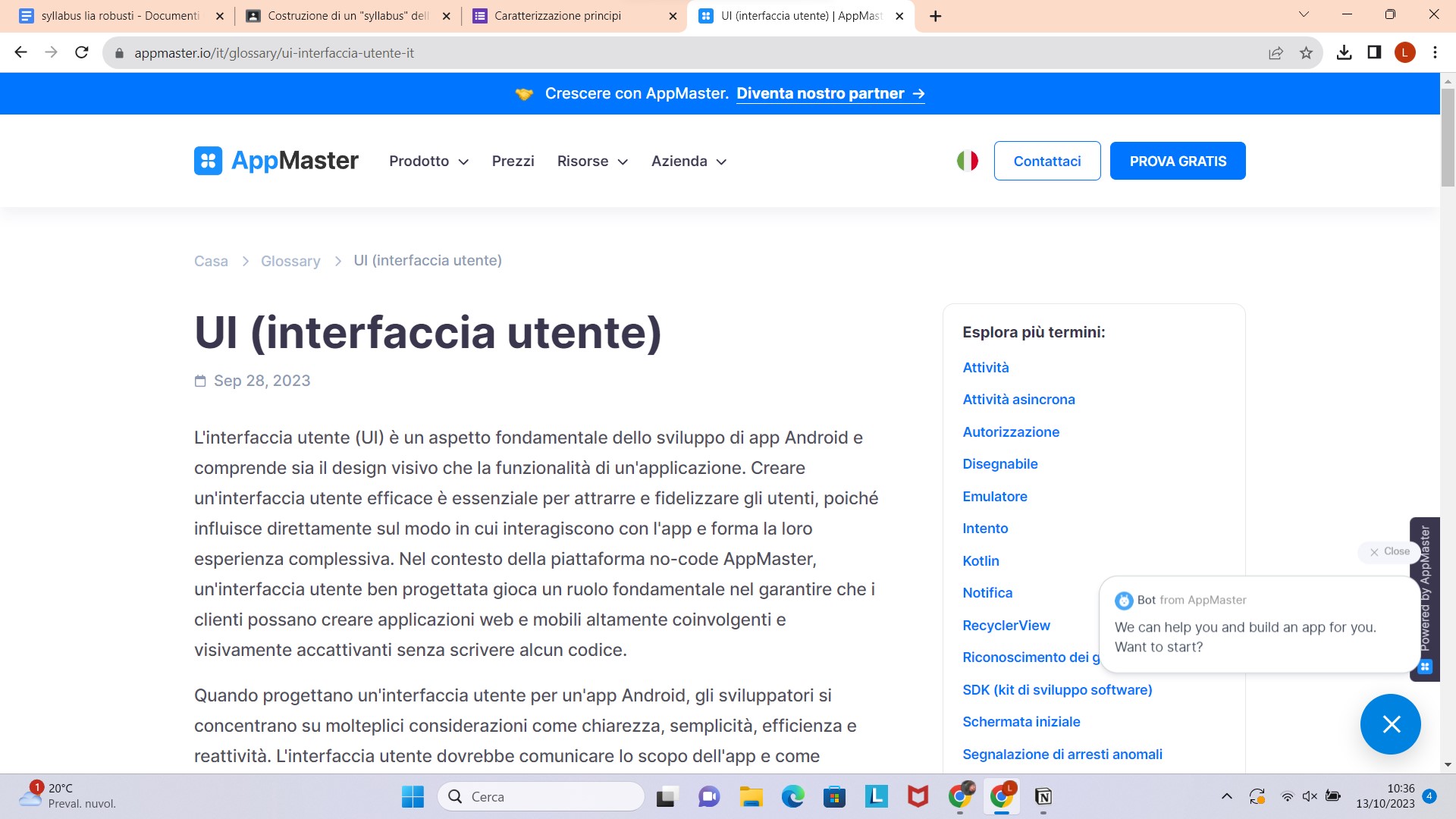

f.02 App Master crea applicazioni con strumenti e pannelli facilmente raggiungibili, fornisce un'interfaccia drag-and-drop, gli elementi visivi sono progettati per essere sufficientemente grandi da consentire una facile interazione e le azioni più comuni vengono posizionate in posizioni ottimali sullo schermo. f.03 Windows 10 invece mostra elementi consigliati e preferiti, lasciando tutte le applicazioni secondarie nell’elenco a lato con una dimensione ridotta.

Applicabilità a oggetti fisici e prodotti

f.04 Fisicamente, nelle tastiere ad esempio, i pulsanti sono più o meno tutti identici, senza nulla che risalti in maniera evidente, in quelle da gaming (E-blue, Simpletek) i tasti più utilizzati nel gioco hanno un diverso colore e risultano la prima cosa su cui cade l’occhio.

fig.01

fig.01

fig.02

fig.02

fig.03

fig.03

fig.04

fig.04

Enunciato originale del principio

Use large objects for important functions (Big buttons are faster). Use small objects for functions you would prefer users not perform.

Use the pinning actions of the sides, bottom, top, and corners of your display: A single-row toolbar with tool icons that “bleed” into the edges of the display will be significantly faster than a double row of icons with a carefully-applied one-pixel non-clickable edge between the closer tools and the side of the display. (Even a one-pixel boundary can result in a 20% to 30% slow-down for tools along the edge.)

While at first glance, this law might seem patently obvious, it is one of the most ignored principles in design. Fitts’s law (often improperly spelled “Fitts’ Law”) dictates the Macintosh pull-down menu acquisition should be approximately five times faster than Windows menu acquisition, and this is proven out.

Fitts’s law predicted that the Windows Start menu was built upside down, with the most used applications farthest from the entry point, and tests proved that out. Fitts’s law indicated that the most quickly accessed targets on any computer display are the four corners of the screen, because of their pinning action, and yet, for years, they seemed to be avoided at all costs by designers.

Multiple Fitts: the time to acquire multiple targets is the sum of the time to acquire each. In attempting to “Fittsize” a design, look to not only reduce distances and increase target sizes, but to reduce the total number of targets that must be acquired to carry out a given task. Remember that there are two classes of targets: Those found in the virtual world—buttons, slides, menus, drag drop-off points, etc., and those in the physical world—keyboards and the keys upon them, mice, physical locations on touch screens. All of these are targets.

Fitts’s Law is in effect regardless of the kind of pointing device or the nature of the target. Fitts’s Law was not repealed with the advent of smartphone or tablets. Paul Fitts, who first postulated the law in the 1940s, was working on aircraft cockpit design with physical controls, something much more akin to a touch interface rather than the indirect manipulation of a mouse. The pinning action of the sides and corners will be absent unless the screen itself is inset, but the distance to and size of the target continue to dictate acquisition times per Fitts’s law just as always.

Fitts’s Law requires a stop watch test. Like so much in the field of human-computer interaction, you must do a timed usability study to test for Fitts’s Law efficiency

(fonte: Bruce Tognazzini, First Principles of Interaction Design)

pagina visitata 83 volte dal

09/11/2023